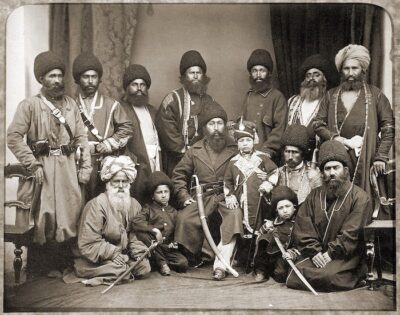

The Taliban in Afghanistan (the very epitome of conservative and backward reactionaries) have a very developed and intricate system of clans. Ethnically, they belong to the Pashtuns, the dominant ethnic group in the country. And they can trace their origins back to ancient families and their respective groups and sub-groups. Justice is something that is settled between the elders of the families, often through talks and negotiations. Everyone is someone. There is a strong emphasis on the defence of women, family, property and land, and an unspoken final factor, namely that every Pashtun ideally recognises no master, that he is completely personally independent.

It all reminds me to some extent of the nobility in Europe.

While ordinary people in our latitudes hardly know the name of their great-grandfather. We are family-less social nomads. And we have to rely on the help of the state in case of crime or other vulnerability. A nobleman, on the other hand, calls his cousin, who in turn calls an uncle who happens to know someone in the right department. While your house is still sealed by police tape and you have to seek help from the social services. Family and “networks” are for the rich, while the middle classes have to rely on society’s meagre support. A lot of people probably feel cheated.

Are we living in times when the clan mentality is on the way back? Perhaps. On the one hand, we have a number of immigrant groups living in strong family ties, and they are to some extent challenging the justice system in various parts of the country, and on the other hand, we see clan structures among the wealthy and successful. Some crime is also clan-based, and there is a lot of romance around, for example, the Italian mafia in films etc., which of course influences the culture. We also find family and clan culture in science fiction literature. In Frank Herbert’s novel Dune, the universe is ruled by powerful aristocratic families. Herbert’s writings have influenced the genre to a great extent, as well as George Lucas’ original Star Wars films.

Is equality before the law and public courts a thing of the past? Will our clan overlords in the future settle who was right and who was wrong?

I would argue that we have always had some sort of clan-based law, but it is not visible in a country where most people belong to the same clan structure. Only when challenged by other clans it becomes apparent. Sweden was only a few decades ago an ethnically homogeneous country, and people knew what the order was. The Svea clan ruled, and there was a legal apparatus that acted as their extended arm. People accepted this. Perhaps things worked a little differently up north with the Sami clan, or in the south with the Skåne clan, but for the most part there was a common understanding of the legal system, culture etc.

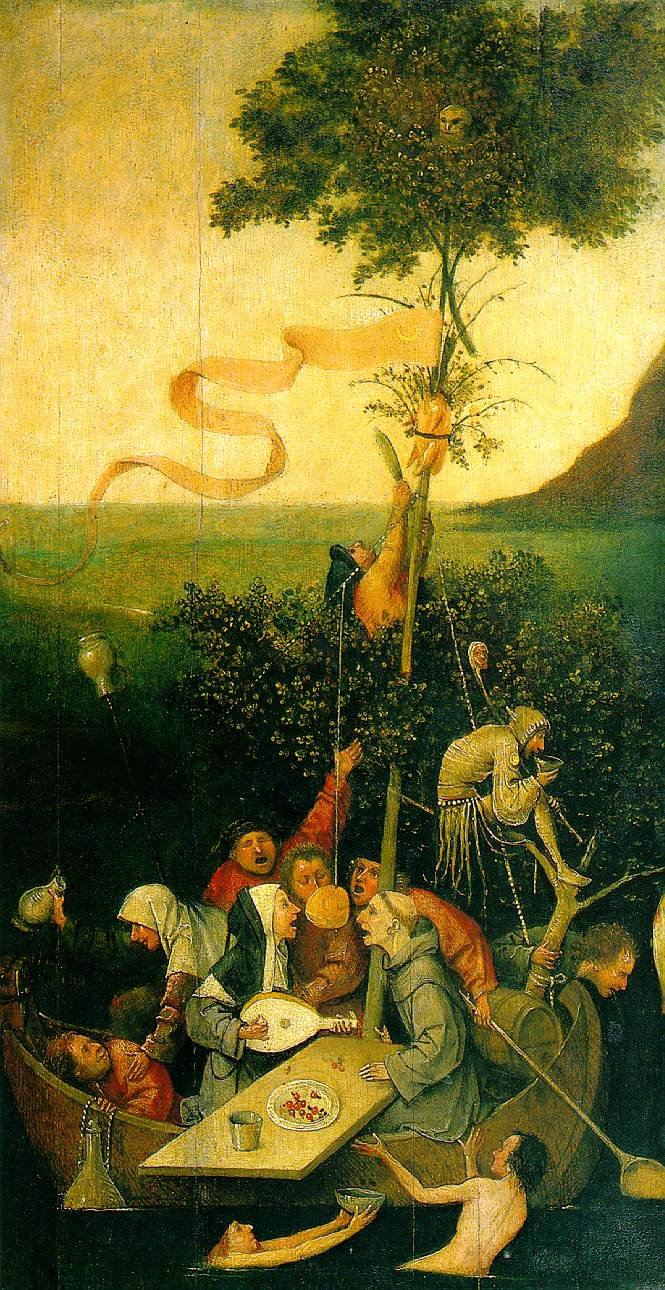

In older times, the northerners also organised themselves into clans and family circles. A friend of mine who is an archaeologist (specialising in the Nordic countries), however, says that during the Viking Age people more often joined together in brotherhoods. A number of men joined together, along with wives and concubines, fitness for battle was probably an important factor. They lived together in longhouses and farms, and joining other similar groups they could go out to war or conquest, etc. The Nordic culture was characterised by meritocracy. If you had to go to war, or protect the farm, your family might not be enough, so you gathered even stronger people around you. And the league of brothers were probably the best form of social organisation in those times and latitudes. Disputes were settled at court meetings, where justice could be sought, and judgements and punishments handed down.

Society was probably more organised than the school books attribute to the Dark Ages. It was not ruled by an omnipotent king of God’s grace, but by an intricate network of families and groups, whose external rules were often characterised by consensus (even if disputes within the groups occurred) and therefore the rules could be codified in decrees, law books, etc. Europeans have often sought order and progression, and the streamlining and regulation of law and justice was probably seen as an extension of the will of the clans and confederations.

But we are not there today, as our system is being challenged from various quarters, and it is not certain that the Svea clan holds the club any longer.