When our modern liberalism came into vogue, also known as social liberalism, it embraced equality, social safety nets and greater state responsibility. This happened in many countries (especially in Europe) after World War II and beyond. Liberalism became a kind of super-ideology, and there were international organisations that accelerated its progress, including the United Nations.

When our modern liberalism came into vogue, also known as social liberalism, it embraced equality, social safety nets and greater state responsibility. This happened in many countries (especially in Europe) after World War II and beyond. Liberalism became a kind of super-ideology, and there were international organisations that accelerated its progress, including the United Nations.

Swedish social democracy has many similarities with this global political force. And the constant tussle between left and right was mostly about different kinds of liberals arguing about details, whether the municipal tax should be 25 or 30 per cent, not whether we should have a municipal tax at all. There was consensus on most major issues.

The right to free association was one of the fundamental freedoms that was slowly and quietly abolished with the introduction of liberalism. And it’s about the right to associate with the people you want. Many people smile at this because it seems obvious, but of course it is not. A shopkeeper is required to let everyone into his shop, and if he does not, he can be accused of discrimination or even racism. Although he owns the shop, manages its operations, and has an ethical right to free association, in practice he does not have that right.

But why would he choose not to let in people of a certain ethnicity? some people ask, it sounds unreasonable and wrong.

But we don’t really have the right to pry into the shopkeeper’s world of ideas, if he doesn’t want to let in tramps, women, foreigners or clowns – that’s his business. And we do not have the right to interfere. But we do have the right to vote with our feet – if we think the shopkeeper is unpleasant, we go to another shop. And in the best of all possible worlds, the shopkeeper realises that his right to free association could jeopardise the business if he doesn’t play his cards right, and invites the vast majority. This is where civil society can self-regulate. This is how it is supposed to work in a truly free society.

But that freedom has been taken away from us, and is now managed by the government with its authorities and functionaries. Our politicians think they manage our human relations better than we do. Many worry that it would be a harsher society if we were given the right to free association and free speech, that there would suddenly be discrimination here and there. Many citizens willingly give up their freedoms and rights because they are afraid of the world and life itself, and the consequences of a truly free society.

Perhaps a moderate amount of freedom is best? Presumably this is what contemporary liberalism is all about, that people should not go overboard? That we should live in a harmonised society?

It is against this background that normal politicians suddenly want to censor journalists, for example because they want to interview a president of a neighbouring European country. It sounds crazy, but unfortunately it’s true. Tucker Carlson’s interview with Vladimir Putin was not welcomed by EU politicians, and the interview had not even been broadcast. So, they did not disagree on the content, but on the right to meet Putin and to conduct and, above all, broadcast such an interview. Putin is sometimes compared to Stalin and Hitler because of the war in Ukraine, but surely such people should also be interviewed? There is a great public interest, and it can be instructive to know how such individuals behave and reason. No matter how the programme is slanted, or not; it is up to the citizen to absorb the information and form an opinion, or insight.

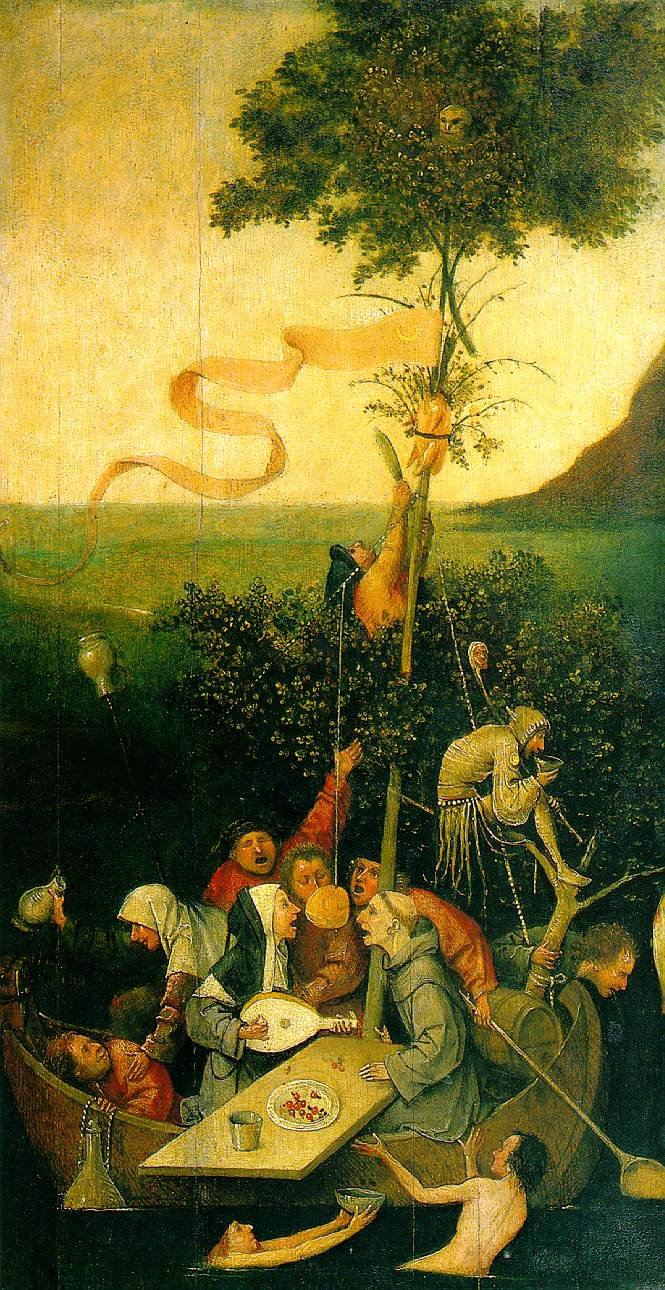

Many would probably describe our politicians as scared and indoctrinated, locked in their bubble with colleagues and yes-men. They do not see the world outside, and do not realise that people are drifting away from them, that the world is changing. Sure, by all means, but there is also something deeply evil about it all. This is not the first time in world history that politicians have tried to censor journalists. We have read about it in the history books. We know what it’s all about. It’s nothing new. But now it’s not about grandfather or great-grandfather, we are in the middle of it ourselves. The world is changing before our eyes. Here and now.